“The tragedy of oldage is not that one is old, but that one is young.”

— Oscar Wilde

Some patients find reassurance in gray hair, or so it seems.

Years ago, as a sandy-haired young faculty member in my mid-30s, I made rounds with one of our resident physicians. Although he was several years younger, he had a full head of very prematurely gray hair. We stopped in to see an older patient to “staff” the case, that is, have the resident present the patient’s story to me as the faculty physician. We entered the room and introduced ourselves. “Mr. Smith,” the resident said, “This is Dr. Campbell. He is my professor.”

Years ago, as a sandy-haired young faculty member in my mid-30s, I made rounds with one of our resident physicians. Although he was several years younger, he had a full head of very prematurely gray hair. We stopped in to see an older patient to “staff” the case, that is, have the resident present the patient’s story to me as the faculty physician. We entered the room and introduced ourselves. “Mr. Smith,” the resident said, “This is Dr. Campbell. He is my professor.”

The man looked back and forth between the gray-haired resident and me.

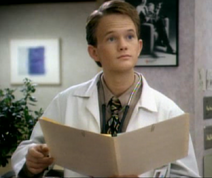

“Yeah, right!” the patient said. “Your professor. Sure. Who is he, really?” At the time, the TV show, Doogie Howser, MD, was still on the air. More than once, I had been told that I looked a bit like the 16-year-old title character. Despite my reassurances, the patient remained skeptical.

“Yeah, right!” the patient said. “Your professor. Sure. Who is he, really?” At the time, the TV show, Doogie Howser, MD, was still on the air. More than once, I had been told that I looked a bit like the 16-year-old title character. Despite my reassurances, the patient remained skeptical.

I knew, of course, that my days of looking too-young-to-be-a-doctor were numbered. I don’t remember when I last heard the comment, but it has been decades since anyone was confused about whether I have enough years behind me to do what I do.

Recently, I have been thinking more about the other end of the career. When is a physician too old to continue?

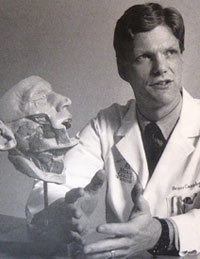

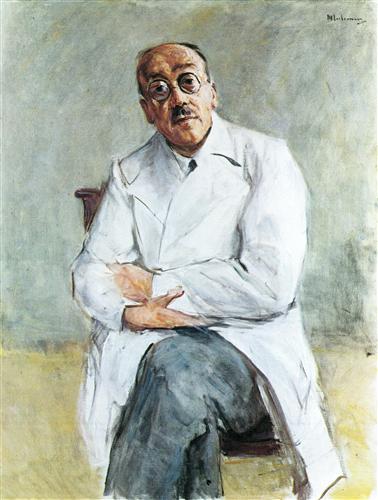

A recent article, "The Aging Surgeon," [Katlic MR, Coleman J, Annals of Surgery (Aug) 2014; 260(2): 199-201] brought the topic into better focus. The authors re-tell the story of Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch, an inventor of medical devices and a giant of surgical innovation. He began his remarkable career after graduating medical school in 1902, developing innovative limb prostheses for World War I soldiers and creating a pressure chamber that advanced the practice thoracic surgery. He was a surgical leader in Germany, and frequently cared for the rich and famous because of his technical prowess. Of note, although he was not a party member, his relationship to the Nazis has been referred to as “ambiguous.”

A recent article, "The Aging Surgeon," [Katlic MR, Coleman J, Annals of Surgery (Aug) 2014; 260(2): 199-201] brought the topic into better focus. The authors re-tell the story of Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch, an inventor of medical devices and a giant of surgical innovation. He began his remarkable career after graduating medical school in 1902, developing innovative limb prostheses for World War I soldiers and creating a pressure chamber that advanced the practice thoracic surgery. He was a surgical leader in Germany, and frequently cared for the rich and famous because of his technical prowess. Of note, although he was not a party member, his relationship to the Nazis has been referred to as “ambiguous.”

Dr. Sauerbruch is also known for his horrific decline. Toward the end of his career, he became forgetful, moody, and technically inept. As he approached his mid-70s in the late 1940s, he was causing immeasurable harm during even simple procedures. Despite being encouraged to do so, he refused to retire. Unfortunately, his iconic stature apparently allowed him to keep operating until a famous actor died during a procedure in 1948. Despite this, he continued to perform surgery in his home until his own death in 1951.

Older surgeons are subject to the same issues as everyone else. We all experience declining sensory functions, a loss of habitual and controlled analytic memory, and decreased visual-spatial abilities. Despite this, many surgeons, when asked, do not believe that they are in decline. As Dr. Sauerbruch's story confirms, aging and an absence of insight are dangerous when other people’s lives are at stake. There is enormous variability between individuals, but this decline is the basis for mandatory retirement in the US for commercial airline pilots (65), FBI agents (57), and air traffic controllers (55). There are no such requirements for physicians.

Before I went to medical school, I worked as a nurse’s aide in our local hospital. Many of the doctors had been on the staff for decades. At the time, we viewed the oldest of the general practitioners as either “cantankerous,” “doddering,” or “harmless.” The older surgeons tended to be in the cantankerous category. In retrospect, we likely gave them labels for a reason. A few years later, my fellow trainees and I christened the various surgeons under whom we trained as cranky, wise, rigid, steady, inscrutable, or timid. In our view, some of the older doctors “still had it” and others did not. Doing the calculations, I know that many were younger than I am now.

I am approaching one of those birthdays with a zero at the end (Now, you do the math). I experience a twinge every time I can’t recall a person’s name or it takes longer than it should to remember where I left a notebook. I look in the mirror and see only gray. I understand that this wonderful opportunity to perform and teach surgery will not last forever.

Surgeons hear a lot of great things about themselves from patients and family members. Co-workers tend to be positive or to keep quiet. Now that I have read about Dr. Sauerbruch, I am more committed than ever to step aside while I am still safe. I only hope that when someone sees that I am not providing the absolute best care possible that my friends and colleagues will tell me.

And that I will believe them.

Bruce, having self-awareness is an invaluable characteristic---- especially in your field. Proud of you for having the courage to share your thoughts on a subject that can be looked upon with dread and fear by those of us approaching one of those '0' birthdays.

Having reached my 70th birthday I can tell you that if you listen to God, to your heart and soul, you will always know when to stay or go. When I left one career, God opened some delightful new doors for me that I never dreamed were possible. Thanks for sharing these thoughts with us. You have so much to offer to so many.